The oilfields that dot the Niger Delta landscape have a common feature; high flames spewed day and night from the oil production sites. This is gas flaring, a menace that Nigeria has proven adept at failing to stop amid weak regulatory standards and unsustainable production methods oil businesses continue to use.

For decades, oil spills have been damaging the environment, devastating livelihoods of the local population – most of whom are farmers and fishers – and precipitating violent agitations in the Niger Delta region. But gas flaring is also a considerable problem, a sort that accelerates global climate change, extending destructive consequences beyond the Niger Delta area.

Tackling the problem – which means contributing to climate change mitigation – is also creating an opportunity to address the problem of gas shortages that commonly cripple Nigeria’s power generation plants.

A power business chief, Edu Okeke, said his company Azura, the independent power producer based in Edo State, uses 110 million metric British thermal unit (MMBTU), equivalent of thousand cubic feet (mcf) commonly used in Nigeria, to generate 440 MW of electricity.

“Gas is energy,” Mr Okeke said. “But with gas flaring, we are wasting the opportunity to convert the gas to electricity, while also destroying the environment.”

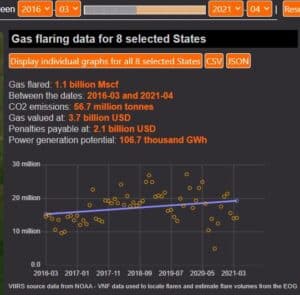

According to data by the Nigerian Gas Flare Tracker, between March 2016 and April 2021, eight of Nigerian states – Delta, Edo, Bayelsa, Anambra, Imo, Rivers, Abia and Akwa-Ibom – flared about 1.6 billion mscf, a volume valued at 3.7 billion USD, with power generation potential of 106.7 thousand GWh but not also without pumping 56.7 million tonnes of Carbon Dioxide into the atmosphere.

Delta State alone between March 2016 and April 2021 flared 415 million Mscf, valued at 1.5 billion USD with power generation potential of 41.5 thousand GWh and also released 22.1 million tonnes of CO2.

READ ALSO: Stella Oduah Dumps PDP For APC

These natural gas when flared into the atmosphere also poses health risks, locals say, apart from the environmental hazards.

Kwale, a community in Ndokwa West Council of Delta State, is surrounded by about 10 flaring sites at production facilities operated by oil companies. Gas flaring has continued to have negative impacts on the livelihoods of the residents as well as their health.

“Fire waves in the air burn everyday,” Efetobor John Omoru, an accountant in a farm in Kwale, said.

He said the heat and hazardous particles from the fire have taken a toll on their farm produce as the moisture in the soil dries quickly.

“Farmers in our community have been greatly affected by the issues of gas flaring. It gets worse during the dry season because of the heat generated by these companies, thereby making the crops suffer,” he said.

Omoru also decried the effect of gas flares on the health of the residents in the community, stressing that the excruciating heat has made the environment almost inhabitable as many people find it difficult to sleep.

“Flares have heated the environment to the extent that we hardly sleep, most especially in the dry season. People get dehydrated fast due to the harsh atmosphere,” he said.

Gas Flaring and Climate Change

Gas flaring is the burning off of associated gas that comes together with oil during production. Flaring has been in practice for decades in Nigeria despite an official ban in place since 1984. A meagre penalty – two USD per mscf of gas flared – was imposed.

But oil companies prefer flaring and paying meagre fines to the government to putting in place an infrastructure to capture the gas and make it useful. They have argued that such infrastructure would be expensive.

According to the authorities, a report says, nearly 80 per cent of the four billion standard cubic feet of associated gas produced by oil companies in Nigeria is utilised or redirected into the earth crust.

The remaining, approximately 700 million standard cubic feet of gas, is burnt off in the open daily at over a hundred sites, causing tons of greenhouse gases to be emitted into the atmosphere. In every mscf of gas burnt, 53.12 kg of carbon (CO2) is emitted. Methane, another greenhouse gas – the most dangerous – is also part of the flared gas.

It is one of the most challenging energy and environmental problems as the practice causes emissions of these greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, thereby causing the greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect is a kind of roofing in the atmosphere that traps heat remitted from Earth that would otherwise escape into outer space, thus causing global warming.

The World Bank’s 2020 Global Gas Flaring Tracker finds that oil production declined by 8% (from 82 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2019 to 76 million b/d in 2020), while global gas flaring decreased by 5% (from 150 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2019 to 142 bcm in 2020). Locally, Nigeria is also seeing a fall but experts say it is inconsequential and gas flaring continues dangerously.

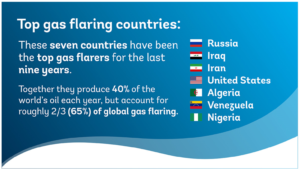

Nigeria, Russia, Iraq, Iran, the United States, Algeria, and Venezuela remain the top seven gas flaring countries for nine years running. These seven countries all together have produced 40% of the world’s oil each year, but account for roughly two-thirds (65 per cent) of global gas flaring.

Gas flaring is a major source of greenhouse gases (GHG) contributing to global warming. In 2020 alone, a report by the Nigerian Gas Flare Tracker noted that 19 million tonnes of CO2 were emitted into the atmosphere contributing to global warming.

READ ALSO: Presidency Should Address Issues Raised By Ortom – Aide

Chukwumerije Okereke, a Nigerian professor of environment and development, expressed worry over the daily standard cubic feet of gas being flared in the country. According to him, the flared gas contributes huge emissions to the climate.

Nigeria is one of the country’s most considerably impacted by climate change effects.

“We should be worried as there is no reason why we should be flaring as much gas as we do in Nigeria,” Professor Okereke said. “There are technologies available for converting the gas to other uses. Reports have it that 65% of households use charcoal, wood to cook in the rural areas.”

“It is beyond comprehension that a country can flare gas as much as we do and still allow women to cook with these hazardous elements. Indoor pollution contributes to the death of women in rural communities, hence, the government should encourage the use of gas for cooking. Gas flaring is the biggest supply of carbon emissions in the country and there is no justification for Nigeria to be flaring,” added the professor.

Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme – Stalled Solution

The federal government in a bid to protect the environment from the adverse effects of gas flaring and also being a signatory to the Global Gas Flaring Partnership, GGFR, the convention for global flare-out by 2030, launched the National Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme in 2016.

This was launched ahead of her commitment to a national flare-out target by 2020, making it 10 years earlier than the global target. It was intended to be a market-based mechanism for ending gas flaring and consequently mitigating climate. However, that, as it turned out, hasn’t been met.

The programme launched by the then Minister of State for Petroleum Resources, Ibe Kackikwu, empowers the minister to take flared gas and commercialise it.

The programme would involve third-party investors or off-takers who must demonstrate technical capacity for the design, construction, operation and maintenance of gas utilisation.

However, five years after the initiative and under a new leadership, the gas commercialisation hasn’t met its purpose – despite a promising start, that even saw a bid call.

To ensure the programme is implemented, the federal government further launched the Flare Gas Regulations 2018 on July 5th, 2018. The regulations provide the legal basis for the implementation of the programme and also introduced new penalties for gas flaring.

It will provide a legal framework for the protection of the environment against the adverse effects of gas flaring, prevent waste of associated gas and build social and economic benefits to Nigeria from gas which might rather be flared during production operations.

The latest data from the programme, according to the Department of Petroleum Resources, DPR, showed that some companies have been awarded the right to process flared gas from 178 identified gas flaring sites.

“Not Stalled”

Speaking with Mr. Paul Osu, Head of Public Affairs, Department of Petroleum Resources, DPR, which manages the commercialisation programme, on why the programme has not been fully implemented over the years, he said, “The National Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme has not stalled. The bid application and evaluation processes for the identified flare sites have been concluded and successful bidders will soon be notified for close out.”

Reacting to the slow pace of progress with the programme, Professor Okereke called for faster policy implementation and monitoring by a statutory agency.

Prof. Okereke said, “I hope the Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme works, I have been told that there are quite a number of interests from the investors and some of them are already in the process of converting the gas that is flared into a number of different end products including CNG, LPG. One can only hope that the commercialisation Programme works because we cannot continue to waste our resources and endanger the livelihood of the host communities.

“Nigeria operates a start and stop approach, we start an initiative that looks so promising today and stop tomorrow. Several deadlines and promises have been made in the past to end gas flaring, many of which have been shifted. We can only hope that the initiative yield a positive result that can end gas flaring.”

Speaking on the recently promulgated Petroleum Industry Act, which upholds the prohibition of gas flaring, except for a few circumstances in which there is no other reasonable option than to flare, Professor Okereke said, “We should applaud the President but you are aware that gas flaring has been illegal for a long time and the penalty to stop it has been very small compared to the damage been caused. Many times, these penalties are not even collected, one can only hope that the new provision in the PIA adds to the gas flaring elimination plan. The ascension of the bill is only one step in the right direction, it is very robust, strong and professional but we can only hope that the can of worms of corruption does not eat up the good work that has been done in that regard.”

Gas To Power – Missing Opportunity

Nigeria has an installed electricity generation capacity of nearly 13 thousand megawatts. But the country is ever able to generate and distribute less than three thousand MW to final consumers on average. Nigeria’s notorious power sector crisis is a major bottleneck to economic growth.

Apart from the liquidity crisis affecting the sector, insiders also complain about the shortage of gas required to power the thermal plants. Higher rate of Nigeria’s electricity is generated from gas-fired plants.

In April 2020, the Transmission Company of Nigeria lamented that gas shortages were crippling power generation, preventing optimal generation of power into the national grid.

“With the current situation therefore, the distribution companies that have the capacity to pick more load are unable to, as TCN strives to distribute what is generated into the grid equitably among DisCos nationwide,” TCN’s spokesperson, Ms Ndidi Mba said in 2020. She said some power plants were producing at zero rate.

Yet Nigeria has vast gas resources, which the country has failed to translate to power generation. Experts, therefore, say that the flared gas is a sort of missing opportunity to create more resources to fuel the power generation plants and make them work more optimally.

The Executive Secretary of the Association of Power Generation Companies, Dr. Joy Ogachi, said flared gas could have been captured to generate thousands of megawatts of electricity.

This story was produced under the NAREP Climate Change Media 2021 fellowship of the Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism.

![Biafra Motherland Warriors Attack Nigerian Security Agents, Kill Officers [Video]](https://newsoneng.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Biafra-Motherland-Warriors.jpg)